'Smoke and mirrors': Who was the real Andy Warhol?

Getty Images

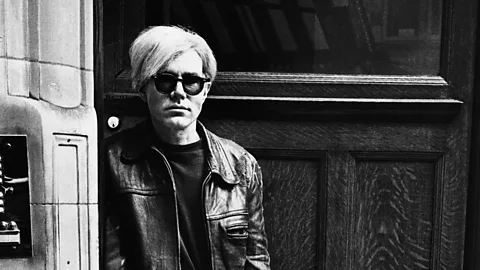

Getty ImagesWith his famous wig and shades, Warhol cultivated a mysterious, enigmatic persona. Now a new exhibition with unprecedented access reveals the man behind the elaborate façade.

"If you want to know all about Andy Warhol, just look at the surface of my paintings and films and me, and there I am. There's nothing behind it," the visual artist − famous for his Campbell's soup can paintings, Brillo box sculptures and screen prints of film stars − told journalist Gretchen Berg in 1966.

Bob Adelman Estate/ Westwood Gallery NYC

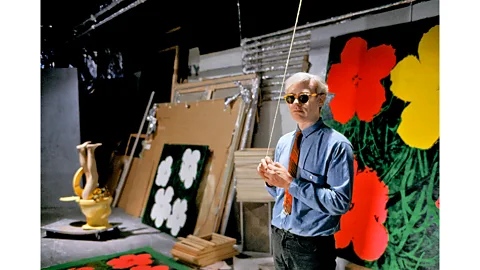

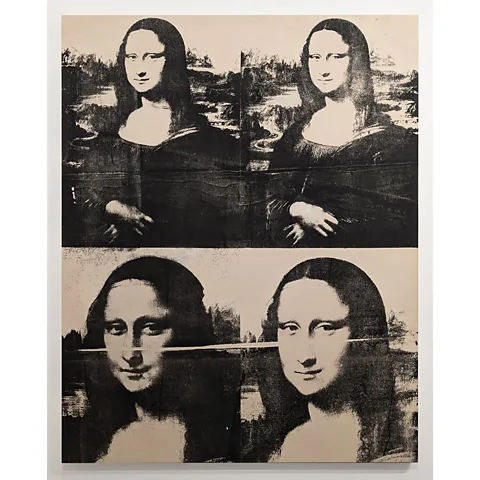

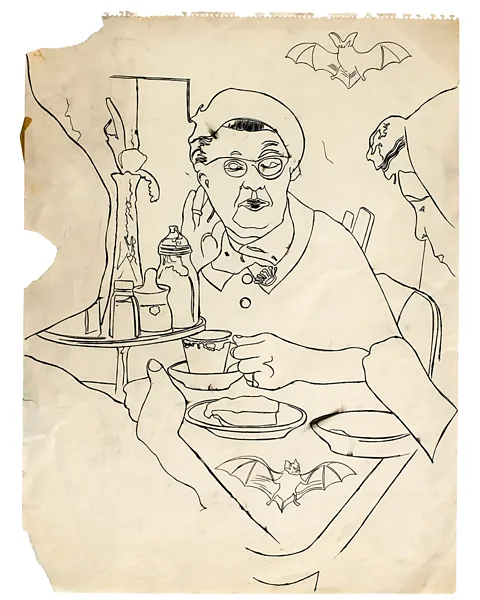

Bob Adelman Estate/ Westwood Gallery NYCA new exhibition in West Sussex, UK, Andy Warhol: My True Story, disagrees. Spanning 11 rooms at Newlands House Gallery in Petworth, the show reveals the hidden depths of this key figure in pop art − a movement that peaked in the 1960s and drew on popular culture, advertising and mass media. It demonstrates the gulf between the artist's public persona as a slick-quipping pop icon, and the private Andy, a profoundly shy and sensitive character. Family ephemera, early sketches unearthed from the archives, and intimate photographs that have never been exhibited all offer a new perspective on a figure as familiar to us as the Marilyn and Mona Lisa prints that are on display.

The show is curated by British art historian and author Professor Jean Wainwright, a world expert on Warhol and a longstanding friend of the Warhola family (Andy later dropped the "a"), who pours her extensive knowledge into a major exhibition on the enigmatic artist for the first time. A decade after Warhol's death in 1987, Wainwright, then writing a doctorate on Warhol's audio tapes, travelled back and forth to his home town of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania to interview the artist's inner circle and to work her way through the more than 2,000 cassette recordings made by Warhol of the events he attended, the conversations he had and his private thoughts. The Andy Warhol Foundation has now placed the tapes under embargo until 50 years after his death (2037), meaning that people can listen to them but not transcribe them. So, no-one knows their contents better than Wainwright. "I had been given access in a way that nobody had before," she tells the BBC. "I got a real sense of him as a person."

Andy Warhol Foundation/ Licensed by DACS, London/ Courtesy Westwood Gallery NYC

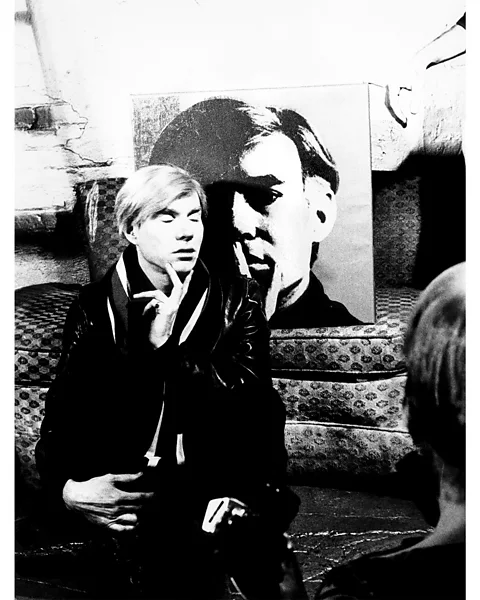

Andy Warhol Foundation/ Licensed by DACS, London/ Courtesy Westwood Gallery NYCSay the name "Andy Warhol", and a very particular image springs to mind: an aloof and effortlessly cool member of the New York avant-garde art scene; a style-setter dressed in dark glasses, leather jacket and spiky "fright" wig, who attracted a constellation of stars to the hedonistic gatherings at his studio, The Factory. "We think of him being a party animal and the epicentre of New York," says Wainwright, but that perception of him changed as her research deepened. "I realised as soon as I started listening to the tapes and meeting the family that he was such a multi-faceted person," she says, describing herself "like a detective piecing things together".

The biggest misconception about Warhol, maintains Wainwright, is "that he didn't care and he's all about surface". A 1971 Gerard Malanga photograph titled Andy Warhol in a pensive moment at the Factory, shown for the first time in a museum, helps dispel such myths. Taken the day he learnt that Valerie Solanas, who shot him in 1968, had been released from prison, it depicts a downcast Warhol with a distant look in his eyes. Later in the exhibition, a sketch from 1985/6 – of a skull and a laser focus on a small area of torso – illustrates the profound physical and mental effects of the attack, so grievous that Warhol needed to wear a corset for the rest of his life. A year later, he would die from complications following surgery.

"Actually, he did deeply care," says Wainwright. "He made himself into that character [with wig and glasses], but underneath, there was so much going on, so many human traits: self-doubt, worry, nervousness, shyness, anxieties – all these things that we don't necessarily associate with Warhol." In his diaries, for example, he described being handed a microphone at a Studio 54 anniversary party in 1978, and being unable to articulate any thoughts into speech: "I just made sounds… and people laughed," he said.

Andy Warhol Foundation/ Licensed by DACS, London/ Courtesy Daniel Blau

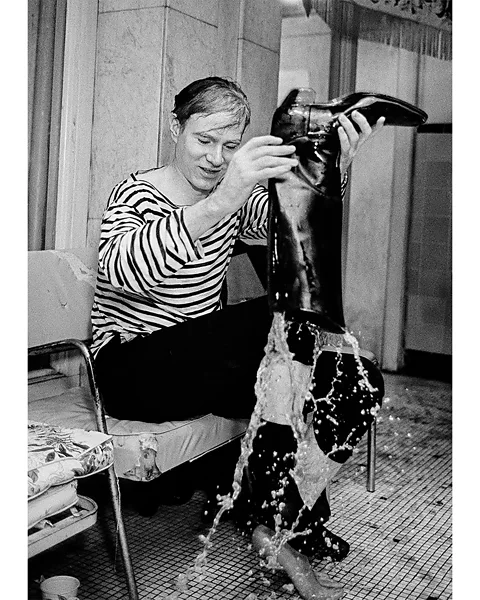

Andy Warhol Foundation/ Licensed by DACS, London/ Courtesy Daniel BlauFurther clues to the real, more tender Warhol seep through the exhibits. Downstairs, a 1956 drawing of a topless man reclining as tiny hearts wing their way like butterflies from his left hand, hints at Warhol's sexuality, which was not openly expressed. While upstairs, his good humour is apparent in an unseen Bob Adelman image from 1965 that shows a soaking wet Andy laughing as he pours water from a boot after being pushed into a pool by actor and close friend Edie Sedgwick.

'Surprisingly domestic'

Most surprising of all, perhaps, is the central role played by family in the life of this cult figure, communicated in the exhibition through private artefacts: postcards written to his mother from exotic locations, each beginning "I'm OK" or "I'm alright", and taped interviews revealing that he was also a doting uncle who'd play jokes on the children, such as pretending to be on the phone to someone famous. "We loved to visit him in New York," says his niece, Madalen Warhola on one of the tapes, which can be listened to in the exhibition. "His townhouse was like Never-Never Land [with] robots, tons of candy, toys and lots of Bazooka bubble gum."

More like this:

• How 'dollar princesses' brought US flair to the UK

For a famous artist, Warhol's private life was surprisingly domestic. His widowed mother Julia, whose legacy is felt throughout the exhibition, lived with him from 1952. She had migrated from what is now eastern Slovakia, and the two spoke her native Rusyn together and were regular attendees at a Catholic church. Warhol's footage of her from 1966 offers a rare glimpse into their home: the washing up accumulating by the kitchen sink, the net curtains and the chipped paint – a scene that is far removed from the upscale lifestyle we might imagine.

Billy Name Estate/ Courtesy of Dagon James/ printmatters.uk

Billy Name Estate/ Courtesy of Dagon James/ printmatters.ukFew people would know this side of him, says Wainwright, due to his "smoke-and-mirrors façade" and his tendency to "put out a different kind of image into the world". Speaking to the BBC in 2019, Eric Shiner, former Director of the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, describes Warhol as "a great artful dodger" who enjoyed sharing misleading information. "He really did like to get people off the scent," he continues. "When asked where he was born, he would sometimes say Cleveland, sometimes say Buffalo, other times say Pittsburgh… It was all in an effort to create a mythology around himself so that no one ever really knew the real Andy Warhol."

Photographers also remarked on this elusive quality. "When I was photographing him, it felt like I was going after smoke," recalled David Bailey in 2019, whose rarely seen image of Warhol, Hallway (1973), appears in the show. "It's right there in front of you, you can see it, but when you reach out to grab it, it disperses and disappears."

As for his striking look, that too was smoke and mirrors. It not only hid his insecurities (thinning hair, the requirement for eye ), but also helped fabricate his distinctive brand. "He'd learnt how to make yourself memorable from cinema," says Wainwright, and he made himself into something "instantly recognisable", just like his soup cans.

Bob Adelman Estate/ Westwood Gallery NYC

Bob Adelman Estate/ Westwood Gallery NYCHe also hid behind pithy soundbites, but even some of these, including the "surface" quote at the start, were reputedly fed to him by others, with Warhol simply agreeing with the statement. Often, he deliberately allowed others to build his image on his behalf. "I'm so empty today. I just can't think of anything," he told an interviewer in 1966. "Why don't you tell me the words and they'll just come out of my mouth">window._taboola = window._taboola || []; _taboola.push({ mode: 'alternating-thumbnails-a', container: 'taboola-below-article', placement: 'Below Article', target_type: 'mix' });